How Well Does Oda Write the Straw Hat Women in One Piece?

Since I did the women of Naruto before, I decided to look at the women of One Piece by Eiichiro Oda, and, boy, is there a difference. It’s not that One Piece has perfect women, but the issues aren’t in their stories. So let’s head for the Grand Line and see what’s there.

I’m going to take a look at the main women and a couple smaller ones since, sadly, women are the minority of the Straw Hat pirates. But despite the limited numbers, the women that are present are not completely stereotypical and none of the main women have stories contingent on men or romantic relationships. The character most obsessed with love and romance is actually Sanji, the cook of the Straw Hat crew, who falls for any beautiful woman he see and happily does anything Nami or Robin ask with hearts in his eyes.

The best thing about the women in One Piece is the fact they are friends with men without crushing on or being involved with any of them. It’s something that is sorely lacking in media, especially when geared to boys. Women are so often cast in the romantic role even when their major stories or plots do not include it. To not only allow women to have male friends who aren’t interested in them (san Sanji) but then to present that as the rule rather than the exception gives women’s stories equal treatment as men’s and improves their characters and the series as a whole. Men are who they are because of what happened in their lives, and, in One Piece, women are too.

Romantically-Inclined Characters

Just as there are romantically-inclined women in real life, there are a few in the world of One Piece. At the moment, I can only recall a couple women throughout the series who had men or romance as a noticeable part of their stories. Let’s take a look at these first, since romantic tropes were a major complaint in Naruto.

Charlotte Lola

We meet Lola in the Thriller Bark arc as one of the victims who’d lost their shadows to Geko Moria. Lola’s personality is first introduced as a warthog zombie in love with and wanting to marry Absalom. Moria had stitched Lola’s shadow to the warthog zombie, which is why it had many aspects of her personality. The obsession with marriage was one of them. The real Lola had escaped an arranged marriage and now wanted to marry for love. By the time she meets the Straw Hat pirates, Lola had proposed to men more than four thousand times.

While this desire to marry is presented as a quirky part of her character, she is never upset to be rejected nor discouraged or ashamed that she isn’t married yet. She just wants to find someone to marry for love. More than that, her search for a husband is secondary to her real story as a captain of the Rolling Pirates who have been trapped on Thriller Bark. She is shown as a strong swordswoman (through the Lola zombie), who is brave and stands by her convictions (as she does when she refuses to run from the daylight even though it would kill her). Her want for a husband doesn’t drive her story or her character’s motivations, her predicament and her care for her crew does.

Now, if you read my “Kishimoto Can’t Write Women,” you might be wondering why I am forgiving of Lola, but not of the Mizukage, who is also a strong woman with a quirk about being married that is played for laughs. The first difference is that the Mizukage is just another among a large group of women trapped in stereotypes and based on romance. Lola is one of the rare ones played like that in One Piece. Also, the Mizukage doesn’t want to marry per se, she’s upset that she’s not married “at her age,” making her comments about marriage come from a negative place. Lola is not upset she’s not married and is never dejected at a refused proposal. Her lack of marriage is never presented as a failure in her. She wants to add to her life and doesn’t see marriage as something she’s lacking for not having it already. This is why I’m all right with Lola but not the Mizukage.

Boa Hancock

The other female character that is driven by romance is Boa Hancock, one of the Seven Warlords of the Sea, a pirate authorized by the World Government. She’s the only female character that I can think of whose love for a man becomes a driving motivation to her actions.

After being immune to Hancock’s charms and showing his selfless nature, Hancock falls in love with Luffy. This leads her to help him get to Impel Down to save Ace and during the Summit War, despite her distrust of people and men in particular. She is an empress of the Kuja tribe and a pirate captain, but we often see her acting based on her desire to help and protect Luffy. If you remove her love for Luffy, her character would be and act differently, as Hancock becomes more emotionally open after meeting and falling for Luffy.

In addition to her romantic plotline, Hancock’s Devil Fruit abilities are based in using lust against both men and women. In essence, love and lust are major components of her character. But like Lola, she is an outlier female character, not the average. Boa Hancock may have a big focus on love and lust, but that is her story, not the story of every woman in the series.

She also has many negative traits that are often attributed to beautiful women: arrogance, manipulation, and the belief she can get away with anything because of her beauty. But these are a result of her living as a slave to the Celestial Dragons, who treated her as subhuman. She manipulates because she will not be manipulated by others again. She looks down on others, because she lived for years being looked down on. In order to never be a slave again, she will do anything to get her way and protect herself.

Charlotte Pudding

I am hesitant to fully label Pudding’s story as romantic since Pudding herself is constantly conflicted with her feelings. As a member of Big Mom’s family, she’s placed in the role of the deceptive innocence. Outwardly she shows people a loving, happy personality, while privately she’s ruthless and conniving. I want to mention her though, because of the reason for her sudden attraction to Sanji.

Cast as Sanji’s bride meant to kill him, Pudding initially finds Sanji’s weakness for women and heartfelt honesty as a failure in his character. She mocks his genuine care for others, but it’s that same honesty and care that changes her. Having been ridiculed all her life for her “ugly” third eye, Sanji’s ability to see beauty in it, in effect accepting Pudding in a way no one else did, gives Pudding the validation of worth that her own family denies her. So her rather abrupt change of heart toward Sanji is not based in his looks or wealth or position, but his honesty, kindness, and acceptance. That is a stronger basis for a romantic storyline than simple physical attraction.

The Straw Hat Pirates

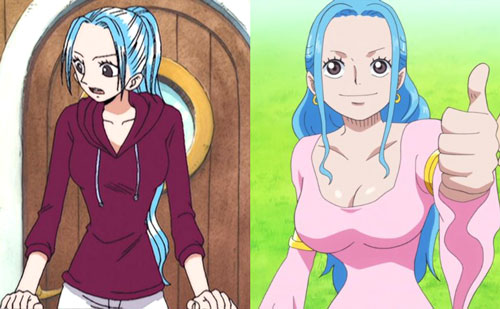

While there are only two official female members of the Straw Hat Pirates, I’m including a third in this section. Vivi is with the crew long enough to count as an honorary member, and she considers joining the crew before choosing to remain in Alabaster.

Nami

Nami is the first major woman introduced and the second person to join up with Luffy, though she’s fourth in officially joining the crew as their navigator. While she does use feminine wiles to trick or manipulate people (mostly men) into doing what she wants, and further into the series her proportions and dress become exceedingly male fan service, that’s the extent of her stereotypical female tropes.

Like the men in One Piece, Nami’s personality is a direct result of the events of her childhood with her adopted mother, Bellemere, and her adopted sister, Nojiko. At no point does her story lean toward men or romance. Nami’s story centers on a female parent and an all female family. The closest male character is Genzo, who is presented as a father figure rather than a romantic interest.

Her navigation skills, obsessive love of money, and even her manipulation of men can all be brought back to her childhood experiences. Nami shows skill in map making early in her life, a fact the Arlong Pirate exploit for eight years before she meets Luffy. During her life with Bellemere, Nami saw her mother using feminine charm to get what she wanted, which explains why she is ready to use the same techniques on others.

Written poorly, this manipulation of men combined with her fan serviced looks and desire for money could turn Nami into the stereotype of a gold digger or user of men, but Oda escapes most of the negative impacts of such stereotypes on Nami’s character due to the attention he pays to her back story.

Nami’s obsession with money does not come from an unwarranted desire to have it simply because she wants it. For her, money is more than a way to have nice clothes and fancy things, as much as she does enjoy that. A lack of money was why Bellemere had to eat nothing but tangerines at times to keep Nami and Nojiko fed. Money was why Bellemere was killed by Arlong and how the villagers stayed alive. Money was how she would one day free the village of Arlong’s rule. To Nami, money is survival.

It makes complete sense that that deeply engrained perception of money wouldn’t simply go away with Arlong’s defeat. Money is just another way that Nami protects the Straw Hat crew. She’s the one in charge of distrusting the funds for ship repairs, supplies, and food reserves. The crew gets their share only after the needs of the ship are met. This is why her obsession for money doesn’t take a more negative connotation to her character. The reader is able to empathize with her instead of seeing her as a gold-digging stereotype.

Nefertari Vivi

Vivi is the princess of Alabasta, and like many princesses throughout the One Piece series, she is strong, intelligent, and fighting for her country. Little about Vivi falls into a stereotypical princess or “woman’s” role, even when it easily could have.

When Alabasta was going down the road to civil war, Vivi didn’t sit on the sidelines or work within the country to try and make peace. She saw a threat to her people and chose to take the most difficult and dangerous path to uncover the person responsible by infiltrating the criminal organization Baroque Works. When she is exposed, Vivi does everything possible to get back to her people and reveal the truth to the rebel side in hopes of stopping the civil war and saving lives on both sides.

Her desire to save all her people stems from her understanding that the rebels are still her people, who she, as a princess, is meant to help and protect. This belief comes from her understanding of the responsibilities of a ruler, which she has known since she was a child, and not from the stereotypical “soft-heartedness” of a woman. No matter how many setbacks she and the Straw Hat crew face, Vivi continues to put herself in directly in the path of danger in order to stop the war. It is her earnest love of her country and the future of its people that finally connects with those fighting.

The place that could have most easily fallen into a romantic storyline was her childhood relationship with Koza. Oda could have gone the Romeo/Juliet storyline with Vivi and Koza, as they were childhood friends and now the leaders of the two opposing factions. Oda ignores that storyline and instead keeps with his rule that men and women can be close friends without being romantically involved or attracted to one another. In a way, the lack of any attraction or romance deepens the connection (and division) Vivi and Koza have by making it about them and their causes and not each other.

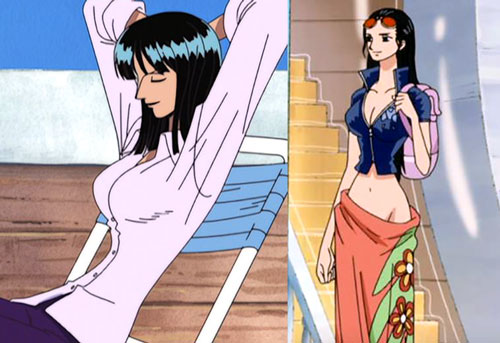

Nico Robin

Like Vivi, Robin is first introduced as a part of Baroque Works and an enemy of Vivi and the Straw Hat crew. She joins Luffy and the others after Vivi chooses to stay in Alabasta, and Luffy agrees to it on a whim, as Luffy tends to do. She is presented as a beautiful and mysterious woman even as she becomes more and more part of the crew, but that is the extent of any female stereotypes. Robin does not intentionally manipulate men like Nami, and she tends to be accommodating to Luffy and the other’s decisions. Robin is also one of the stronger members of the crew in a fight. Her appearance is often geared to male fan service, but not nearly to the extent Nami’s is.

Robin’s back story focuses on her isolation in her village and the absence of her mother. Her motivation to become an archeologist and learn to read poneglyphs stem from her desire to be with her mother and have a real family. Again, Oda reveals a tendency to have a woman’s story center around mother figures and a man’s center around father figures with a focus on found families.

{A notable exception to this is Zoro’s back story, which focuses on his friend and rival, Kuina, the daughter of the dojo’s teacher. Again, men and woman are placed on equal standing and allowed to be friends without condition.}

Robin has several male father-figures within her back story who help her survive, but her main goal as a child was to be in a real family with her mother. She lives the next twenty years just as isolated in the world as she was in her village, and she’s constantly reminded that she shouldn’t be allowed to live because of her knowledge of the poneglyph language. It’s because she’s alone and surrounded by people who want her dead almost all her life that turns her into the (sometimes ruthless) mystery woman we first meet in the series. It’s also the reason that she desires more than anything a family who loves and is willing to fight for her. Family is what matters to Robin.

With the Straw Hat women, Oda not only ignores romantic storylines, but he roots their characters in experiences with familial love that mirrors the motivations of their male companions. Oda doesn’t completely eschew romance in his series, but since the majority of the women aren’t placed in that role, the ones that are don’t feel overdone and tropey.

Flaws in Female Representation in One Piece

No series is without its flaws, and One Piece is no exception. The most obvious problem is a common occurrence in media geared to boys: a limited number of female characters. Of the now ten member of the Straw Hat crew, two are female. Of the twelve pirates labeled the Worst Generation, one is female. Of the Seven Warlords of the Sea, one is female. And, lastly, of the Four Emperors, one is female. It’s as if as long as they have at least one, then they’ve met the quota for women. Oda could do better on evening the numbers a little.

But for the women that are there, while they have complex and nuanced storylines, the way they are drawn and treated by other characters is problematic. Both Nami and Robin start the series with normal proportions and appropriate clothing, a little idealized but not unrealistic. As the series progresses their figures and outfits are more and more created for male fan service, Nami especially. What’s annoying is that Oda has made some very nice, practical, and sexy outfits without hypersexualizing them, but it’s getting less and less common.

The major female side characters likewise become more and more sexualized as the series goes, and they are either idealized beautiful or comedicly unattractive. Men also have strange physical appearances that are remarked on, but men’s unusual appearances are not commented on in the sense of attractiveness, while women with unusual appearances are normally referenced for their unattractiveness to men.

The biggest problem, though, is not the women themselves, but the way men in the series treat them and how men’s actions are viewed. Lechery is far too normalized. While Sanji’s character is for the most part admonished for his lewd behavior by the crew, it is too often mirrored in other men in towns or villages. Brook’s first question to any woman is “May I see your panties?” He’s generally, and often violently, chastised by Nami, but it adds to the normalization of improper behavior and open sexualisation of women. When Kin’emon first meets the Straw Hat crew, he condemns Nami for the way she dresses (at the time in a bikini top) but then acts in ways to keep her minimally clothed for his own enjoyment of her figure.

The majority of the Straw Hat men don’t act this way—Luffy doesn’t appear to have any sexual desires—but what’s there creates an ever present attitude that men will just act that way and there’s nothing that women can do about it. No matter how many times he’s chastised, the moment Sanji gains the ability to become invisible, he heads to a bathhouse to covertly watch women bathe. Brook continues to ask every woman he meets if he can see her panties. Men everywhere continue to sexualize women’s bodies.

Perhaps the most concerning scene in the series is Nami’s shower in Thriller Bark. Absolam enters the bathroom using his invisibility to stay undetected, but goes on to pin a naked Nami to the wall and “inspect” her. This was a scene that didn’t need to happen the way it did. Nami’s vulnerability at that moment is sexualized. That alone was problematic, but Sanji’s reaction to learning it happened only compounded the issue.

Sanji becomes furious when he learns Absalom entered Nami’s bath, but he’s most upset that he, Sanji, couldn’t do it instead. It is not Nami’s person who is the victim, but Sanji’s ability to turn invisible and watch women that has been lost. That is not the message that needs to be sent.

Overall, Oda does a great job in building complex female characters whose stories are presented as equal to their male counterparts. He needs a few classes on unnecessary sexualisation though, and a few on how women’s clothing actually works.

What do you think of the women of One Piece?

That was super well written. It is super annoying to see that female characters were not as sexualized at the beginning of the series but now it is becoming even ridiculous. Rebecca’s outfit is, wow, like what the hell. (mostly she is supposed to be 16).

I never really liked Sanji because of the way he acted in front of girls. I gained more respects when I watched the season with Big Mom, but still, why is he so creepy. Mostly I kind of feel that the majority of the fan base is sexist. Like how many times did I hear that everyone hated Nami. Like why? Everyone likes robin but only because she is pretty quiet. They always call Nami weak and useless, but even if it was true, (I don’t think so), the whole Straw Hat crew are supposed to be friends, like that is the whole point. Usop is pretty weak but nobody cares, cause he is a really good friend.

I feel really bad for Nami sometimes. Like, she is strong, emphatic, she knows how to defend herself but a lot of people do not take her seriously, or they only focus on her body.

My little brother is watching one piece, and now I feel like I really need to talk to him about how this portrayal of women is wrong. Cause I do not want him to think it is normal to act this way towards girls.

But I really agree about the complex personalities that female characters have. I felt like the Eiichiro Oda was doing so well, until his male fan base asked him to be more “entertained” with the girls in the series. It is very annoying, but I still watch it, and like it a lot because the storyline is amazing.

LikeLike

Very well said, I agree with all the points you made!

LikeLike

Awesome essay! I completely agree. I love One Piece, and the character writing is great, but Oda’s casual sexism often ruins it a bit. It’s upsetting – just by acknowledging women as people with agency, he’s already doing better than 90% of shonen, but doing the bare minimum shouldn’t make One Piece stand out. And for the love of god, Oda, it costs 0 Berries to have a gender-balanced cast.

Sanji being used as the channel for Oda’s own creepiness is especially upsetting – Sanji’s kindness is what makes him a beautifully compelling character, and having that kindness and care for others go down the drain whenever he’s horny is cheapens both his character and the series. I completely agree with you that the issue with One Piece’s female characters is rarely the characters themselves (with a few exceptions, e.g. Tashigi on Punk Hazard), but rather the way male characters react to them. It stings that Oda can have so little empathy for the female (and so little understanding of the male) characters that he, outside of the issue of serialization, writes with such grace and tact.

LikeLike